Before my current tortoise, I had owned one other, Izzy. This first tortoise baffled my girlfriend and me. It seemed happy and healthy but refused to eat. We would surround him with rings of various foods recommended to us by the pet store owner, yet the closest he ever came to eating was walking over to a tomato and sitting on it. Each day that we swapped out his old uneaten lettuce for a fresh leaf, our anxiety grew until the day came when Izzy just stopped moving (of course Izzy had managed to make it one day past the pet shop’s one-month return policy, despite never having eaten anything). Though our current tortoise, Vanya, has proved herself much heartier as she nears her sixth birthday, the anxiety returns when we try to understand why she has not eaten in a several days.

Aside from simply “help[ing] us to comprehend huge amounts of data,” (122) Hall also describes other significant advantages of maps and visualizations. They “allow us to perceive emergent properties we might not have anticipated…facilitate our understanding of large-scale and small-scale features…and help us form hypotheses” (122). To be able to harness these properties, I had to decide precisely what to visualize. The tortoise’s movement is the focus of this mapping project, but there are various facets of her perambulations which could be considered. For example, I wished to analyze Vanya’s voyages throughout the entirety of the apartment, but I also felt that capturing smaller details of her movements would be imperative to a full understanding of the tortoise. I also was not sure of what data I needed to collect to reach my goal of enhanced tortoise understanding. For guidance, structuring the experiments and representing the collected data, I adapted Kevin Lynch’s “The City Image and its Elements” from the world of the city to the realm of Vanya and my apartment.

Lynch breaks down any depiction of a city into five functional elements: paths, edges, nodes, districts and landmarks. Paths are potential routes of movement, edges close regions off from one another, and nodes are “the intensive foci to and from which [one] is traveling” (Lynch 47). Districts are groups of paths, edges, and nodes, and landmarks are simply points about which an observer can orient him or herself. My eventual visualizations would need to depict the tortoise’s paths against all possible paths in order to unveil the hidden nodes which are attracting or repelling her. The district and landmark elements of the produced maps would respectively group data points and orient the audience. Finally, to remedy the issue of scale, I utilized multiple levels of experimentation and visualization.

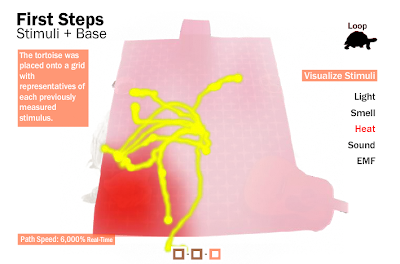

The dimensionally largest of the experiments/visualizations charts the tortoise’s meanderings as animated paths over a bird’s-eye view of my entire apartment. Though bird’s-eye views are helpful in abstracting a large area, one must keep in mind that they represent a false view of the world. For example, the Peters projection controversy, in which global maps such as the Mercator’s were attacked on the basis of “distort[ing] the picture of the world to the advantage of the colonial masters of the time” (Crampton & Krygier). My map must also be viewed critically, as it imparts an impossible view from which conclusions are meant to be drawn. By pairing this bird’s-eye visualization with the other, increasingly objective visualizations, I hope to attenuate the effects of its misrepresentations. Also to aid in the final analysis of the paths, several possible stimuli, such as heat, were measured around the apartment and can be visually laid over several of the maps. Thus, if any of these stimuli pique the interest of the tortoise, they will visually appear as a set of nodes between which the tortoise moves.

Inspiration for the next mapping, a surveillance-style display of the apartment’s actual rooms overlaid with animated paths, was drawn from the long exposure Roomba pictures, MIT’s Senseable city lab projects, and the tangled paths of taxis in the Cabspotting project (http://cabspotting.org/projects/intransit/intransit.html). By combining the animated data with real, human views of the apartment, I hoped to ameliorate the distortions of the bird’s-eye map.

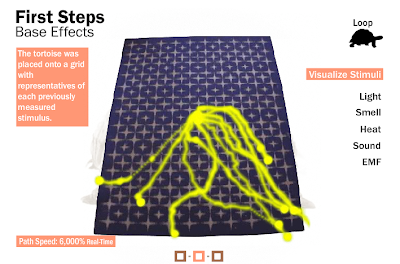

The set of short term experiments highlights the filtering quality of maps, which Hall discusses in Critical Visualization. Though there are myriad factors compelling the tortoise when she is first released, this map allows the viewer to focus on a single specific stimulus and observe its effects on a constrained time and space.

The views from the tortoise-mounted cameras provide the closest study of Vanya’s movements throughout the apartment. Theoretical inspiration was drawn from 16thandmission’s representation of larger spaces through intimate portraits of specific spots, and technical inspiration came from Sam Easterson’s Museum of Animal Perspectives (http://sameasterson.com/map).

To keep the viewer oriented between these many views of the apartment, each representation features a key landmark, the blue carpet. This carpet serves as the starting point for the paths of every visualization and is prominently featured or highlighted to keep the audience correctly positioned in their mental map of the entire space.

Historically, these abilities of mapping and visualizing were reserved for the authoritative powers of nations and businesses, not the common man and his tortoise. Fortunately for me, I live in a time of great upheaval in the cartographic world. Due to technological advances, Crampton & Krygier note that, “In the last few years cartography has been slipping from the control of the powerful elites that have exercised dominance over it for several hundred years.” However, even well-intentioned amateur cartographers produce undesired results. Problems arise because maps not only make sense of the world, but shape it as well. In describing how maps have the power to make reality as well as depict it, Crampton and Krygier quote theorist John Pickles: “Instead of focusing on how we can map the subject…[we could] focus on the ways in which mapping and the cartographic gaze have coded subjects and produced identities” (Crampton and Krygier 15). Maps create a delicate relationship between the understanding and taming of the subject. Therefore, I must be careful in how I use my maps lest I slip from better understanding the tortoise to accidently forcing her into undesired situations. For instance, a correlation between heat and her paths might not mean that she prefers to be in a warmer environment; instead she could just be avoiding the effects of a different stimulus. Overall, since these maps focused more on expanding the amount of information known in regards to the subject, rather than just filtering a larger dataset, I feel that my visualizations will produce greater insight to the mind of the tortoise.

References

(throughout entire documentation blog)

"Critical Visualization", Hall

“An Introduction to Critical Cartography”, Crampton & Krygier,

http://www.acme-journal.org/vol4/JWCJK.pdf

“The Image of the City”, Lynch

This American Life, Episode 110 “Mapping”

http://www.thisamericanlife.org/Radio_Episode.aspx?episode=110

Roomba Mappings

http://www.flickr.com/photos/paulchavady/3458136141/in/pool-roomba/

Museum of Animal Perspectives